Local Industries Buying Local

INTRODUCTION

Did you ever wonder how much local bread your local supermarkets buy? Or how much local auto manufacturers spend on local tires? The process to find this answer may seem complicated, but it is actually relatively simple. Here’s how.

THE PROCESS

Let’s examine how much local beer is purchased by local restaurants in Greater Milwaukee. Start by selecting your Region (Milwaukee-Waukesha, WI MSA 2018 shown below) and heading into the data for Commodity 3106 – Beer, ale, malt liquor and nonalcoholic beer.

STEP 1: FIND THE TOTAL COMMODITY SUPPLY

> Social Accounts

> Reports

> Commodity Summary

> Total Commodity Supply

The Total Commodity Supply for beer is $672,638,420.90. This represents the total beer supply produced in Milwaukee by both Industries and Institutions.

STEP 2: FIND THE REGIONAL INPUTS

> Social Accounts

> Balance Sheets

> Industry Balance Sheet

> Commodity Demand

> Filter for Industry 509 – Full-service restaurants

> Regional Inputs

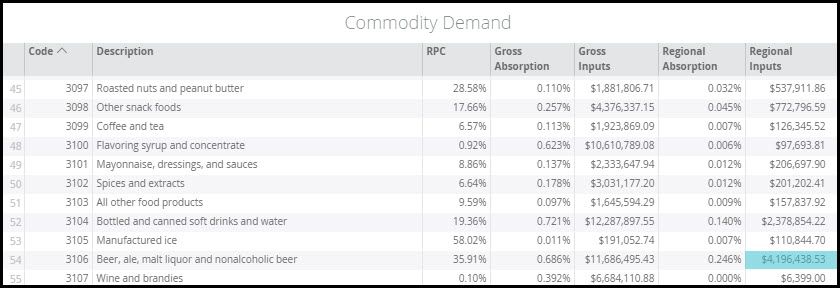

Scroll to Commodity 3106 – Beer, ale, malt liquor and nonalcoholic beer and find the value for Regional Inputs. For the Milwaukee-Waukesha, WI MSA this is $4,196,438.53. Regional Inputs show the amount that restaurants spend locally on beer during the Data Year. Note that the Gross Inputs of $11,686,495.43 represent the total annual spending on beer by full-service restaurants. We then know that local restaurants are spending 35.91% of their beer budget on local brews (RPC = 35.91%).

STEP 3: DIVIDE THE RESULTS

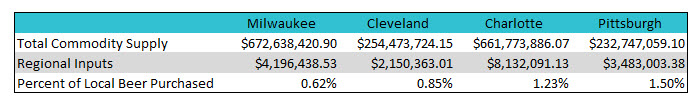

The Regional Inputs of $4M divided by the Total Commodity Supply of $673M tell us that Milwaukee restaurants are buying less than 1% of total local beer production. Given how much beer production occurs in the Region, the percentage of local beer production that is purchased by local restaurants is quite low. The table below compares four cities on the percentage that local restaurants spend on local beer.

STEP 4: EXAMINE EXPORTS

> Social Accounts

> Reports

> Commodity Trade

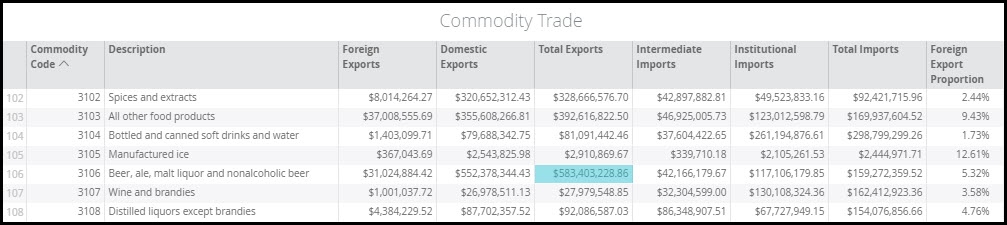

Now we can look at exports. Foreign Exports tells us the total local production that is exported outside the U.S. The Domestic Exports tells us the total local production that leaves Greater Milwaukee but stays in the U.S. The Total Exports is a combination of these two. The Total Exports from Milwaukee is $583,403,228.86. Taking this divided by the Total Commodity Supply of $672,638,420.90 tells us that 87% of the locally produced beer is exported from the MSA. Therefore, 13% stays local – which is known as the Average RSC (Regional Supply Coefficient).

STEP 5: INCREASE LOCAL BEER PURCHASES

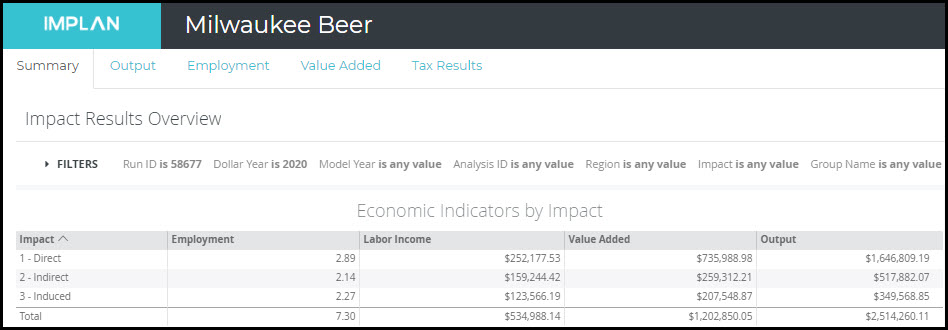

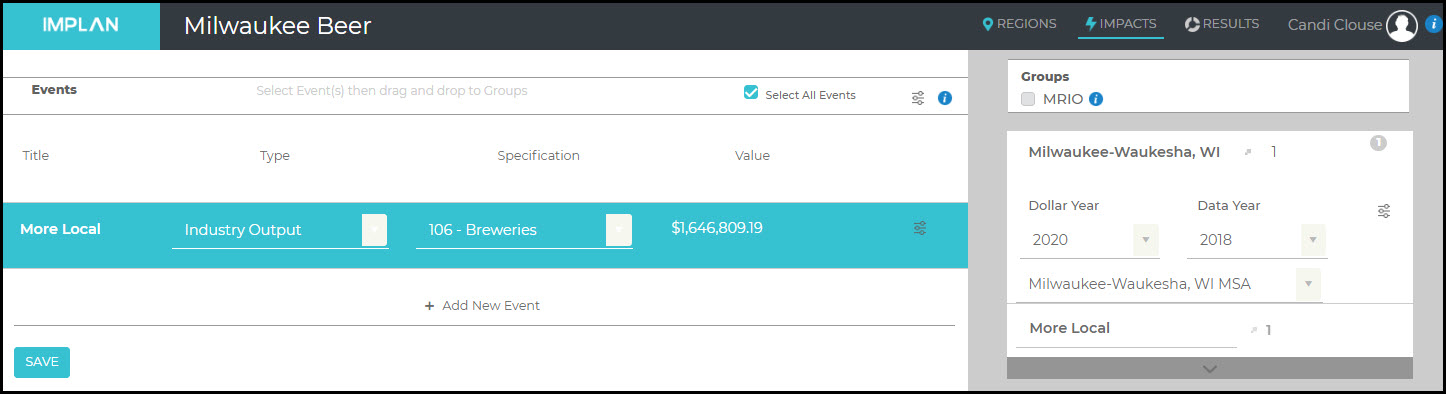

Let’s say local restaurants want to commit to purchasing a full 50% of their beer from local breweries. They are currently spending a total of $11,686,495.43 on beer, so half would be $5,843,247.72. They are currently spending $4,196,438.53, so they would need to increase their local buy by $1,646,809.19. We can run this as an Industry Output Event.

The Results show us that the increase in $1,646,809.19 in local breweries supports a total Output of $2,514,260.11; a multiplier of 1.53. This will support almost 3 employees at the brewery and 4 additional employees in the Indirect and Induced Effects; a multiplier of 2.53.